Pāli is the name given to the language of the texts of Theravāda Buddhism, although the commentarial tradition of the Theravādins states that the language of the canon is Māgadhī, the language supposedly spoken by the Buddha Gotama.

The term Pāli originally referred to a canonical text or passage rather than to a language and its current use is based on a misunderstanding which occurred several centuries ago.

The language of the Theravādin canon is a version of a dialect of Middle Indo-Āryan, not Māgadhī, created by the homogenisation of the dialects in which the teachings of the Buddha were orally recorded and transmitted. This became necessary as Buddhism was transmitted far beyond the area of its origin and as the Buddhist monastic order codified his teachings.

The tradition recorded in the ancient Sinhalese chronicles states that the Theravādin canon was written down in the first century BCE. The language of the canon continued to be influenced by commentators and grammarians and by the native languages of the countries in which Theravāda Buddhism became established over many centuries.

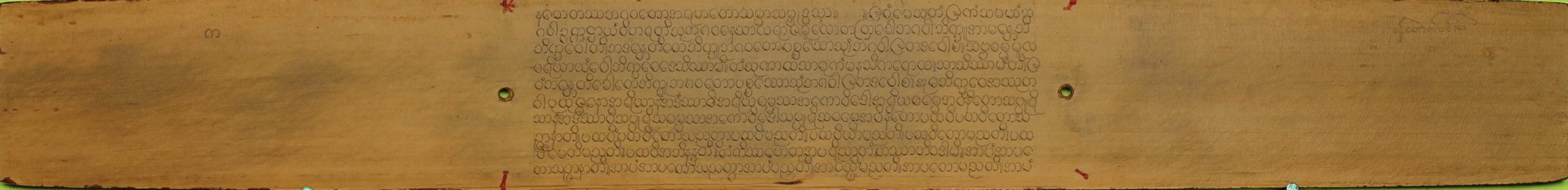

The oral transmission of the Pāli canon continued for several centuries after the death of the Buddha, even after the texts were first preserved in writing. No single script was ever developed for the language of the canon; scribes used the scripts of their native languages to transcribe the texts.

Although monasteries in South India are known to have been important centres of Buddhist learning in the early part of this millennium, no manuscripts from anywhere in India, except for one in Nepal have survived. The majority of the manuscripts available to scholars since the PTS began can be dated to the 18th or 19th centuries CE and the textual traditions of the different Buddhist countries represented by these manuscripts show much evidence of interweaving. The pattern of recitation and validation of texts by councils of monks has continued into the 20th century.

The main division of the Pāli canon as it exists today is threefold, although the Pāli commentarial tradition refers to several different ways of classification. The three divisions are known as piṭakas and the canon itself as the Tipiṭaka; the significance of the term piṭaka, literally “basket”, is not clear.

The text of the canon is divided, according to this system, into Vinaya (monastic rules), Suttas (discourses) and Abhidhamma (analysis of the teaching). The PTS edition of the Tipiṭaka contains fifty-seven books (including indexes), and it cannot therefore be considered to be a homogenous entity, comparable to the Christian Bible or Muslim Koran.

Although Buddhists refer to the Tipiṭaka as Buddha-vacana, “the word of the Buddha”, there are texts within the canon either attributed to specific monks or related to an event post-dating the time of the Buddha or that can be shown to have been composed after that time. The first four nikāyas (collections) of the Sutta-piṭaka contain sermons in which the basic doctrines of the Buddha’s teaching are expounded either briefly or in detail.

The early activities of the Society centred around making the books of the Tipiṭaka available to scholars. As access to printed editions and manuscripts has improved, scholars have begun to produce truly critical editions and re-establish lost readings.

While there is much work still needed on the canon, its commentaries and subcommentaries, the Society is also beginning to encourage work on a wider range of Pāli texts, including those composed in Southeast Asia.